20 Jan Smoke Detected – Early Experience with Surgical Plume

I’m waiting for my wife, Michele, to return home after her day’s work as an operating room nurse involved in robotic surgery. Which reminds me, in my previous blog, I said that I would discuss the laparoscopic phase of my career as a general surgeon so while I wait, please join my reverie.

I’m waiting for my wife, Michele, to return home after her day’s work as an operating room nurse involved in robotic surgery. Which reminds me, in my previous blog, I said that I would discuss the laparoscopic phase of my career as a general surgeon so while I wait, please join my reverie.

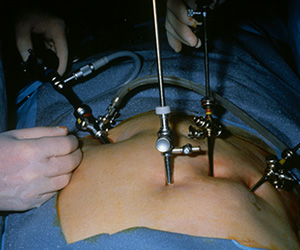

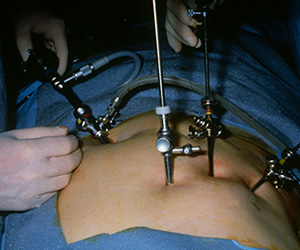

It was 1987 or 1988 when I saw my first laparoscopy. It was the old kind where you had to look through the laparoscope that was clipped to your head band, when insufflation took a while and when release of smoke through a side vent of a trocar meant an immediate loss of pneumoperitoneum and a nasty dose of smoke inhalation. Despite these issues, I pursued the technology through a gynecologic laparoscopy course in Nashville, Tennessee where I met this highly enthusiastic nurse from Grant Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. Kay Ball, who was in my workshop group, watched me vaporize a pig’s gallbladder with a carbon dioxide laser while others in the room pointed their laparoscope toward the pelvis. She invited me to visit Grant and I soon found myself in a laboratory working on laser dissection of pig gallbladders under the tutelage of Dr. Jack Lomano who patiently taught me laparoscopic skills and instrumentation. Further laboratory experience followed at a research lab in St. Paul with our first clinical case performed in late 1988 at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis under an IRB protocol and with the gynecologic assistance of Drs. David Hill and Russell Wavrin.

Our group had the opportunity to report the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy at a national meeting in April, 1989 at the American Society of Laser Medicine and Surgery. Dr. E.J. Reddick then followed with the second such report at the same meeting while Dr. Barry McKernan performed such pioneering surgery in Atlanta, Georgia and may be the very first surgeon to do so in the United States. None of our lives were the same after that but that story will have to be saved for another day.

Pertinent to our topic today was the technical problem that plagued such surgery which was the plume that rapidly filled the abdomen and obscured the lens of the “scope,” not to mention that, when released, the smoke was both nauseating and irritating to inhale. Further, smoke evacuation meant loss of the “pneumo” as well as displacement of retracted viscera. The lens had to be removed and cleaned with alcohol but when replaced back into the warm abdomen, it became covered with condensation further delaying the procedure.

My primary reason for inventing and later commercializing the laparoscopic filter was to prevent inhalation of the smoke by the perioperative team. The marketplace, however, saw the device called, “Plume Away” or “See Clear,” as a vision enhancing device since it kept the lens free of smoke. In a similar fashion, although we introduced our “miniSquair” as a smoke capture device for open surgery, recent research suggests that it may find its greatest use in the operating room as an infection control device. Time will tell as we monitor the marketplace’s response to the product in future blog postings since such research may intensify clinician’s interest in smoke evacuation technology.

My wishes to all for a happy and successful New Year and thank you for spending time with me.